Sweden: what went wrong?

Posted by Stuart in Uncategorized, tags: elections, fascism, swedenSocial Democrats: 30.7% (-4.3), 112 seats (-18)

Moderates (Conservatives): 30.1% (+3.9), 107 seats (+10)

Green Party: 7.3% (+2.1), 25 seats (+6)

Liberal Party: 7.1% (-0.4), 24 seats (-4)

Centre Party: 6.6% (-1.3), 23 seats (-6)

Sweden Democrats (far right): 5.7% (+2.8), 20 seats (+20)

Christian Democrats: 5.6% (-1.0), 19 seats (-5)

Left Party: 5.6% (-0.3), 19 seats (-3)

There are two main issues here I think to be discussed, the first is the failure of the left and the second is the frightening growth of the far-right.

The left’s failure

Right-wing Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt

If the right stays in power until 2014 (ie. if there doesn’t have to be a new election) then it will be the longest time that the left has been out of government since 1920. The most successful time for the right before now had been between 1976 and 1982 although the Prime Minister back then (Thorbjörn Fälldin) was not nearly as right-wing as Fredrik Reinfeldt is today.

Over the last 4 years Reinfeldt has pushed through tax cuts of 100 billion kronor, allowed schools and hospitals to be sold off to private companies, and massive profits to be taken out of publicy funded schools and other essential services. In addition Reinfeldt has made it far more expensive for many workers to be part of the trade-union run unemployment insurance schemes – because of the way the system now works it costs the most in those industries where the risk of unemployment in considered to be greatest (which means that those in low paid service sector jobs often end up paying far more than doctors or teachers). A consequence of this is that many have fallen out of the insurance scheme and have left their unions, resulting in a record collapse in trade union membership.

Perhaps the most outrageous policy Reinfeldt has pushed through has been an assault on sjukförsäkring (sick pay). Under an attempt to reduce what they had claimed was Europe’s highest number of people on sick pay the government have imposed a limit on how long people can claim sick pay for before they are forced to enter the labour market and seek work (which even if you are perfectly healthy is not easy in a country with one of Europe’s highest unemployment rates – as many as 30% of young Swedes are out of work). There have been cases of people with terminal cancer receiving letters saying their benefits are stopping and that they need to start looking for work. As a result of public anger the government claims to have relaxed the rules for those with certain particularly severe illnesses but cases of extremely sick people having their benefits cut continue to emerge in the Swedish media.

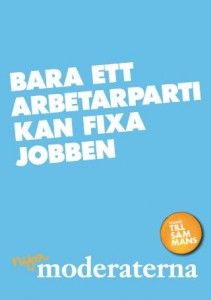

Why has there not been more public outrage about this you might wonder. One strategy which the right have adopted is to claim to be a party for those who work as opposed to those who don’t. They have pitched those who are healthy and who have a job against those who are ill or who are unemployed. ”We want to stand up for those who work while the opposition want to give money to those who don’t” is the sort of statement you commonly hear from Fredrik Reinfeldt. Ironically Rei

At first things seemed to be going well for the left and for years they had been well ahead in the polls – sometimes by as much as 20 points. This lead though, for a variety of reasons, dwindled away and in the run up to the election the right-wing was again in the lead by 5-10 points. Despite a final surge in the last few days with the left strongly highlighting the issue of sick pay they were unable to regain their support and the Social Democrat’s share of the vote fell to a record low – the lowest since 1914.

So what went wrong? Many have blamed the unfavourable media coverage with 3 out of the 4 national newspapers (Expressen, Dagens Nyheter and Svenska Dagbladet) clearly supporting the right-wing government and consistently portraying the Social Democratic leader Mona Sahlin as an uncharismatic loser. This is undoubtedly the case and almost certainly contributed to the left’s defeat. Yet a number of years ago the Social Democrats and trade unions themselves chose to sell off many of the newspapers they once owned, so they too can be held at least partly responsible for the right-wing bias of the Swedish press.

Another thing that was obvious when following the Norwegian reaction to the election is that the Swedish trade unions, as opposed to their counterparts in Norway, have not been particularly active in mobilising support for the left. Whether or not this is due to a general displeasure with the red-green alliance and its policies or has some other cause I’m not quite sure.

But perhaps most important is the tactics adopted by the red-greens themselves and their failure to fundamentally challenge the social and political narrative being put forward by the right-wing government. On far too many issues the red-greens have basically appeared to accept or take for granted the changes which Reinfeldt has been trying to impose on Swedish society. Take for example the so-called ‘jobbskatteavdrag’ (job tax reduction) which has involved income earned through work being taxed at a lower level than income earned through other sources ie. pensions or benefits. This is part of Reinfeldt’s tax cuts which have seen 100 billion kronor of state revenues slashed and are, according to him, fundamental to the government’s attempt to create jobs. Instead of reversing the jobbskatteavdrag the red-greens had decided, in their alternative budget, to keep 90% of the right’s tax cuts and instead cut pensioner’s taxes down to the reduced level currently paid by a worker.

Although Mona Sahlin and the red-greens repeatedly said that they would put welfare before tax cuts, by talking about reducing tax for pensioners as opposed to reversing the jobbskatteavdrag they clearly played into the hands of the government’s tax cutting agenda. Equally the red-greens refused to offer any bold alternative of large-scale investment or to fundamentally challenge the role of profit and private enterprise within the public sector. Only the Left Party’s leader Lars Ohly talked about banning companies from skimming profits away from schools and hospitals while the Greens and many within the Social Democrats didn’t seem to have a problem with it whatsoever.

Yet despite the failure of the red-green’s watered down programme some Social Democrats seem to believe the poor election results are in fact a result of them moving too far to the left, of forming an alliance with the Left Party (who, if you believe many on the right, are still a bunch of unreformed communists who want to overthrow the democratic system). The Social Democratic party’s secretary or leader of the Stockholm region (I’m not quite sure which) came on to the radio the day after the election to say that marginally increasing property taxes and taxes on the rich was a ”very strange way to get the middle class on board” and that next time they will have do more to appeal to the better off. Interestingly Sweden has among the most class-divided voting in Europe -- it’s estimated that among those earning above £50,000 a year around 90% vote for the right whereas immigrants, the poor, sick and unemployed overwhelmingly vote for the left (but unfortunately are much less likely to turn out to vote).

Not everyone agrees with this view of course. Some Social Democrats understand that their future lies in mobilising the working class, immigrants, the poor, those who live in the more deprived surburbs, those who are disillusioned with politics. And they understand that in doing so they will need to work closely with the unions. As for the radical left the only party currently with any national significance is the Left Party who have worked closely with the Social Democrats. Some in the party’s newspaper Flamman have begun to debate their future and what went wrong (the Left Party fell slightly from 5.9% to 5.6% and lost 3 seats). It has been argued that they should do more to distance themselves from their communist legacy or that they could have been a more energising force in Swedish politics if they had joint male and female leaders. Many also feel that the red-greens were too ‘nice’ to the right-wing government during the campaign. Whether or not the Left Party should remain as a slightly more radical version of the Social Democrats, tied down as part of the three party red-green alliance, is something which hasn’t received so much attention.

When I was in Stockholm at the time of the election I attended some protests, saw some speeches and talked to some socialists there. One of those I saw speaking was Left Party leader Lars Ohly. His speech wasn’t bad and he mounted a strong attack on the policies of the right-wing government. Inevitably though his party’s reputation for radicalism has been tarnished by joining the red-green alliance and failing to move the Social Democrats sufficiently to the left. Sweden does still, from the impression I get, have quite a vibrant radical left compared to Scotland. As well as the Left Party there are of course other minor far left parties and Sweden also has one of the strongest anarchist movements in Europe which includes the syndicalist union the SAC. In addition there is a feminist party called the Feminist Initative, led by former Left Party leader Gudrun Schyman. I saw a lot of their posters up around Södermalm in southern Stockholm although FI ended up with a national share of under 1%, down slightly on last time.

Rise of the far-right

Fascist leader Jimmie Åkesson

The rise of the far-right is another extremely worrying trend we can observe from the election. The Sweden Democrats, a party with its roots in the Swedish neo-nazi movement, took 5.7% of the vote which is a doubling of the share they received last time and over the 4% threshold meaning they now have 20 seats in the Riksdag (Swedish parliament). The party’s share varies a lot from one part of Sweden to another: in their base of Skåne in the far south they averaged around 10% and in one neighbourhood near Malmö they took 35%. In Stockholm the party’s support is much lower at around 3%.

Despite the SD’s success there is definitely a lot of opposition to them from throughout Swedish society and many Swedes are determined to prevent their country moving in the same way as Denmark. There the nationalist, anti-immigrant Danish People’s Party have been given enormous influence by the more established right-wing parties who rely on their votes in parliament. As a result Denmark now has one of the strictest immigration policies in the whole of the EU and in recent years we have seen a hysteria in Denmark around Muslims and the role of Islam. Politicians on both the right and left in Sweden have said they won’t touch the SD with a poker and that neither will they alter Sweden’s immigration policy (which is currently among Europe’s most liberal) just because of pressure from the far right. Whether or not this position holds up in the long-tern we’ll need to wait and see. Already before the election the government had started deporting large numbers of Iraqi refugees from Sweden as they argue it’s now safe for them to return.

There has been a dispute on the left in Sweden among what tactics are best if the far-right is to be defeated. In the run up to the election a number of SD rallies were broken up or disrupted by anarchists and others on the radical left. A protest I was at briefly in Stockholm involved hundreds of people surrounding a rally by SD leader Jimmie Åkesson and blowing vuzuzelas in a successful attempt to drown out his speech (check out the video below). Some though, such as Left Party leader Lars Ohly, have criticised such tactics, saying they are anti-democratic and risk allowing Åkesson to portray himself as a victim.

“The only way to deal with people with racist, xenophobic and generally populist views – like the German National Socialism of the 1920s – is through a determined dialogue that we never abandon … I believe that it was precisely the refusal of the other parties, from left and right, to debate with the SD that allowed them to grow from nothing to 6% of the vote. If we had had the debate, the SD might have got into parliament, but with far fewer seats. In fact, they could have been kept out of parliament altogether”.

I’m not sure if I agree with him fully here. While it is certainly essential that we expose the far-right’s prejudice and lies there is always the danger that when you bring a party like the SD into the debate you further legitimise them and give their message a degree of respectability. Although their message shouldn’t be hard to disprove through rational argument it is unfortunately the case that facts don’t always win over prejudice. Where I think Mankell is absolutely right is when he talks about how the SD’s success is a symptom of large number of Swedes feeling left out by the mainstream parties:

“People vote against something rather than for it. In this case, people are looking for a scapegoat for their own miseries. It is the unemployed, the ill, those who feel themselves marginalised and cast out, who turn in their powerlessness against the established parties and vote for those who reach out to them. The SD becomes the only decency they find in a political landscape where everything else is hypocritical and forsworn. The SD listens to them. In the SD’s programme they find their own thoughts, their own anger, their own fears.”

It is precisely the policies of Fredrik Reinfeldt and his right-wing coalition, with mass unemployment, privatisation and a further weakening of the welfare state, which have made it easier for the SD to get their message across. The far right’s success almost always comes at times of social hardship and uncertainty, when people are fearful and don’t know who to blame. If the SD’s success is not to be repeated in 2014 then either the government need to radically alter their policies or the left needs to take back control of the debate on jobs and welfare.

Entries (RSS)

Entries (RSS)