Recent Comments

- ZeitgeistWorker on Shitegeist

- RT Farty Kremlin Party | A Thousand Flowers on Shitegeist

- Javier Sobrino on Scotland and the Basque Country: the struggle for independence

- Gorbachev on Prostitution, the abolition of the victim and post-modernism's defence of the status-quo

- Andy Bowden on Class politics or anti-semitic conspiracies? Why David Icke, Ron Paul and Alex Jones are dangerous to the Occupy Movement.

Tags

afghanistan austerity britain BNP climate change Con Dem coalition demonstration drugs economy edinburgh education elections environment events evil megacorps fascism feminism fighting cuts glasgow greece health internet knobheads Labour Lib Dems moral panic music news police protest racism science SDL sexism sexuality SNP strikes tabloids Tories tv unemployment unions USA war women's rights workers' rightsArchives

- June 2012

- May 2012

- March 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

-

Authors

- admin

- And

- Andy Bowden

- Brogan

- CelticEwan

- David

- Erofeeva

- Euan Benzie

- Frenchie

- ImSpartacus

- Jack

- James McIntyre

- James N

- Kirsty Kane

- Liam M

- Liam T

- lovebug

- LydiaTeapot

- Meghan

- Muzza

- Neil B

- neldo

- Sarah

- Scottish Socialist Youth

- Snowball

- Socialist Pharmacist

- Sophie

- Squeak

- Stuart

- syebot

- TheWorstWitch

- Wavejumper

Feminism, Pornography and the Fight Against Patriarchy

The following is an essay I wrote, and have recently submitted, for my Sexualities class. A bit long perhaps but the blog’s been kind of short of stuff recently and I thought it might interest some people. Have included the bibliography in case anyone wants to do some further reading.

The following is an essay I wrote, and have recently submitted, for my Sexualities class. A bit long perhaps but the blog’s been kind of short of stuff recently and I thought it might interest some people. Have included the bibliography in case anyone wants to do some further reading.

In this essay I will discuss the issue of pornography which has divided feminists for decades and was, above all else, the defining issue of the so-called ‘feminist sex wars’ of the 1980s. For radical feminists, pornography is widely seen as a form of male violence against women and is believed to contribute to a patriarchal and heteronormative ideology in which women are reduced to objects existing purely for men’s sexual gratification. Many of those liberal or socialist feminists who support pornography on the other hand emphasise its supposed potential to bring about sexual liberation and openness and to allow women to more freely express their sexual needs and desires in a world where traditionally only men have been seen as enjoying a sexually active role. Such feminists claim also that any form of censorship would be inherently detrimental to the rights of women and other historically oppressed or marginalised groups. Although the definition of pornography among feminists and academics is widely disputed I will, for the purposes of this essay, accept the dictionary definition of pornography as being “printed or visual material containing the explicit description or display of sexual organs or activity, intended to stimulate sexual excitement” (Oxford Dictionary, 2011).

While the above definition is largely neutral and would encompass a diverse range of erotic material I feel it is important to place most of my focus on those forms of pornography most prevalent within society and which, it can reasonably be assumed, have the greatest impact and influence within the sexual sphere. In this essay I will attempt to explore in more detail some of the feminist debates around pornography, making particular reference to recent developments and research which has been carried out on the issue. Fundamentally important to any understanding, from a feminist perspective, of pornography and how it operates is the issue of power relations and inequalities between the sexes. I will discuss, in detail, the capacity of pornography to either assist or hinder in the building of a more egalitarian and sexually liberated society. For an understanding of what such a society may look like I will, in particular, draw upon prominent radical feminist writers such as Millett and Dworkin who have been instrumental in having sexuality recognised as a sphere through which gender relations built upon male dominance and female submission can be recreated and reinforced.

- Background to the debate

The emergence of the so-called ‘second wave’ of feminism in the 1960s coincided which what is widely referred to as the sexual revolution. At this time many people began to rebel against the traditional religious and family-based notions of sexual morality which had regained support and prominence in the 1950s. Growing tolerance towards, for example, sex outside marriage, homosexual relationships and public expressions of sexuality went alongside the development of new methods of birth control, heralding a major shift away from the view of sex as existing ideally for procreation within marriage and in favour of an embracing of sex for recreation. During this period in many countries homosexuality was legalised and restrictions on abortion also began to be lifted. Pornography too was legalised in a number of countries, the first being Denmark in 1969.

Many feminists, according to Jeffreys (1990: 227), initially looked upon the changes surrounding the sexual revolution as a positive development and embraced the work of sexologists such as Masters and Johnson. As she writes “it is important to understand the great feeling of liberation that women experienced when they were suddenly able to talk about sex with other women and see themselves as sexual actors” (Jeffreys, 1990: 227). At this time, according to Jeffreys (1990: 232-233), feminists generally adopted a “male model of what constituted sexual liberation” with women expected to “initiate male sexuality and become efficient, aggressive sexual performers”. There was Jeffreys (1990: 239) claims “no understanding that men and women existed in a power relationship and that male and female sexuality were constructed through material relations of power and powerlessness such that they could not be changed easily by an act of will”. Increasingly however, attention to issues such as rape and male violence were to lead, from the early 1970s onwards, to a more critical analysis of the role of sexuality and its social construction under patriarchy. One of the most prominent and influential of the early radical feminist writers was Kate Millett who in 1970 published the book Sexual Politics.

Millett in her book focusses largely on society’s views and norms around sexuality as expressed through a number of prominent male writers such as D.H. Lawrence and Henry Miller, highlighting the extent to which it mirrors patriarchal roles and norms about male dominance and female submission. Millett (1970: 23) writes that “coitus can scarcely be said to take place in a vacuum; although of itself it appears a biological and physical activity, it is so deeply set within the larger context of human affairs that it serves as a charged microcosm of the variety of attitudes and values to which culture subscribes. Among other things, it may serve as a model of sexual politics on an individual or personal plane”. By ‘politics’ here Millett means what she describes as “power-structured relationships, arrangements whereby one group of persons in controlled by another”.

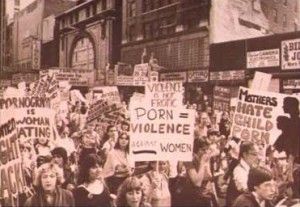

Throughout the 1970s there was a surge in the number of feminist writings focussed around sexuality. One of the examples of this is Against Our Will by Brownmiller which drew attention to rape as a practice central to men’s dominance and power over women. Pornography too became an increasingly important focus of feminist anger with Andrea Dworkin among its most prominent opponents. In 1977 Dworkin (1977: 200-201) gave her first speech on the subject of pornography describing it as “the propaganda of sexual fascism”, claiming that it represented a “new campaign of terror and vilification” being waged against women (Dworkin, 1977: 200-201). Pornography, according to Dworkin (1977: 201-202), is based on the “debilitating lie that the sexual humiliation of women for fun, pleasure and profit is the inalienable right of every man” and “actively promotes violent contempt for the integrity and rightful freedom of women”.

- Pro-porn backlash

Pornography and feminism have many things in common. They both focus on women as sexual beings. Pornography dwells on the physical act of sex itself; feminism examines the impact of sex upon women-historically, economically, politically, and culturally… Pornography is one of the windows through which women glimpse the sexual possibilities that are open to them. It is nothing more or less than freedom of speech applied to the sexual realm. Feminism is freedom of speech applied to women’s sexual rights… Both pornography and feminism rock the conventional view of sex. They snap the traditional ties between sex and marriage, sex and motherhood… In other words, pornography and feminism are fellow travellers. And natural allies. (McElroy, 1995).

The anti-pornography movement which had, by the early 1980s, gained considerable support and strength within the feminist movement and come to be represented, perhaps most prominently by Dworkin, MacKinnon and Russell in the US and by Jeffreys and Itzin in the UK, prompted a backlash by many feminists. One of the milestones in the development of a more sympathetic position to pornography was the 1982 Barnard Conference on sexuality which was held in New York and attended by a group of socialist and liberal feminists. One of those in attendance was Gayle Rubin who later published the paper Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of Sexuality, offering a substantially different analysis of sexuality to that prevalent within radical feminism. The basis of her argument is that different forms of sexual behaviour have, as a result of a legacy of religious-inspired moralism, been placed on a hierarchy with some seen as ‘good’ and healthy and others as ‘bad’ and immoral (Rubin, 1984: 281). Among those seen as ‘good’ are sex which is heterosexual, takes place in private and within the context of marriage and is non-commercial. ‘Bad’ sex on the other includes sex which is homosexual, casual or promiscuous or which involves sadomasochism, pornography or the exchange of money. It can also involve paedophilia which Rubin (1984: 281) refers to euphemistically as ‘cross-generational’ sex. Rubin (1984: 275-284) believes that a progressive approach to sexuality would involve eradicating social stigma relating to sexuality, championing sexual variation and defending the rights of sexual ‘minorities’.

Particularly in the US an issue which galvanised opposition to the radical feminist analysis of pornography is its perceived support for censorship. Those feminists supportive of pornography often claim that their opponents want to give the state the power to ban or censor any form of erotic material, moves which they believe would directly damage the struggle for women’s liberation and for equality between the sexes. Nadine Strossen (1995: 30-32), for example, writes that:

freedom of speech consistently has been the strongest weapon for countering misogynistic discrimination and violence, and censorship consistently has been a potent tool for curbing women’s rights and interests. Freedom of sexually oriented expression is integrally connected with women’s freedom, since women traditionally have been straightjacketed precisely in the sexual domain, notably in our ability to control our sexual and reproductive options… All censorship measures throughout history have been used disproportionally to silence those who are relatively disempowered and who seek to challenge the status quo. Since women and feminists are in that category, it is predictable that any censorship scheme – even one purportedly designed to further their interests – would in fact be used to suppress expression that is especially important to their interests.

- Ignoring patriarchy

What can perhaps be seen to unite some of the approaches and arguments used by some of the above writers sympathetic to pornography is their lack of focus on the continued existence of power structures and hierarchies and on the failure of modern society to achieve anything approaching real and meaningful equality between women and men. Pornography is assumed to offer both men and women equal opportunities through which to express their sexual desires and needs while the influence of patriarchal norms and power differences in shaping how men and women differentially experience sex are glossed over or ignored. Equally scant attention is paid to the increasingly influential role played by the commercial and largely male-controlled porn industry in creating narrow and restrictive norms around gender and sexuality.

Gayle Rubin’s analysis of sexuality, while perhaps providing some insight into society’s attitudes towards certain forms of sex, does not take into account the power differences existing between women and men under patriarchy. It also risks simply replacing one form of social pressure with another. Stark (2004: 278-279) writes, for example, that it “merely reproduces the conservative patriarchal dichotomy between madonna and whore. Sex radicals simply reverse the valuation attached to the two sides: here bad girls are to be celebrated for their rebellion and audacity, while good girls are scorned and mocked as boring, repressed and obedient.” A genuine sex radicalism would, Stark (2004: 280) writes, mean “recognizing structures of inequality and oppression, working towards egalitarian relationships, and aligning with those (whether minorities or majorities) who do not have social or political power – such as women and children hurt in pornography and prostitution.”

The centring of the debate around censorship is also arguably misleading. Few radical feminists have ever called for state censorship on a mass scale, advocating instead either laws against misogynistic hate speech similar to those that exist in many European countries against incitement to racial hatred or, alternatively, the establishment of a system whereby women are able to sue porn-producers for any harm experienced either through the production or distribution of their material (ie. the Dworkin-MacKinnon Ordinance). The straightforward belief that any form of state intervention is inherently detrimental to the cause of women’s rights can, in addition, be criticised as simplistic at a time when various forms of gender equality legislation have made a positive difference in other areas of life. Moreover, to equate freedom for the porn industry with freedom for women to express and enjoy their own sexualities is rightfully seen as absurd by many of the feminist opponents of commercial pornography.

The very meaning of sexual freedom itself within a patriarchal society has also been questioned and critiqued within radical feminism. In a highly stratified and unequal society in which patriarchal gender norms are widely seen as both natural and inevitable it is unrealistic to assume that unrestricted sexual freedom would benefit both men and women equally. As Stoltenberg (1990: 67) explains, freedom and justice cannot be separated from each other with freedom being the “result of justice” for those groups which have been historically oppressed and not the other way round. According to Stoltenberg (1990: 67-68):

The popular concept of sexual freedom in this country has never meant sexual justice. Sexual-freedom advocates have cast the issue only in terms of having sex that is free from… institutional interference, sex that is free from being constrained by legal, religious and medical ideologies; sex that is free from any outside intervention… Sexual freedom has never really meant that individuals should have sexual self- determination, that individuals should be free to act out of that integrity in a way that is totally within their own right to choose. Sexual freedom has never really meant that people should have absolute sovereignty over their erotic being. And the reason for this is simple: Sexual freedom has never really been about sexual justice between men and women. It has been about maintaining men’s superior status, men’s power over women; and it has been about sexualizing women’s inferior status, men’s subordination of women. Essentially, sexual freedom has been about preserving a sexuality that preserves male supremacy.

- Where we are today

In the decades since the height of the so-called ‘feminist sex wars’ in the 1980s there has been a massive increase in the size and scale of the porn industry and pornography has become an increasingly accepted and mainstream part of cultural life. In the US alone around 13,000 new pornographic film titles are released every year and worldwide annual profits for the industry were estimated in 2006 at $96 billion (Dines, 2010: 47). Increasingly porn use has become almost universal for young males and the vast majority of young women, although generally far less frequent consumers of pornography, have viewed pornographic content at least one. A recent study carried out across the Nordic countries, for example, which interviewed 14-18 year olds, found that 99% of young males and 86% of females had come into contact with pornography (Sørensen and Knudsen, 2006: 49). At the same time as pornography has flourished, other aspects of the sex industry have also expanded massively such as prostitution, strip clubs and sex tourism. Expressing the frustrations of many feminists at such developments, D.A. Clarke (2004: 153-154) writes:

In the twenty-some years of my adult life as a feminist – despite passionate and well-informed efforts and despite limited victories in many other areas of political struggle – we seem to have made zero or negative progress in challenging or restraining the men who buy and sell, rent or lease, women and girls. Nor have we reduced the appetite of men … for grotesque imagery of female humiliation, pain, and fear. The twin industries of pornography and prostitution have boomed worldwide and the degree of misogyny deemed acceptable in everyday cultural life has ratcheted upwards to levels I would not have believed possible.

Considering the sheer scale of the pornographic industry today and the extent to which it has entered the cultural mainstream it is reasonable to assume that it shapes our sexual behaviour, attitudes and gender norms in a number of complex ways. As Gail Dines (2010: 47-48) notes “the scale of the pornography industry has important implications. In a profound sense, the entertainment industries do not just influence us; they are our culture, constituting our identities, our conceptions of the world, and our norms of acceptable behaviour”. The simplistic assertion by many that pornography is ‘fantasy’ and as a result has little effect on how people live their lives must therefore naturally be discarded by those serious about understanding pornography’s role in contemporary society. I will now look in more detail at the images coming out of the commercial porn industry, the messages they portray and how individual men and women relate to, and are affected by, such images.

- Images of violence

One of the most fundamental arguments presented in opposition to pornography by radical feminists has been that it is a form of male violence against women and consists of images displaying hatred and contempt. This allegedly violent nature of pornography has however been disputed by a number of liberal and socialist feminists. Dworkin has, for example, been heavily criticised for focussing on the very worst and most extreme examples while largely ignoring the types of pornography most commonly viewed or purchased. Avedon Carol (1994: 42-43), a founding member of Feminists Against Censorship, writes that during the late 1970s and early 1980s she watched and analysed a significant amount of pornography and “found few portrayals that could honestly be described as ‘violence’”. Carol goes so far as to claim that “pictures of dominant males were rare” and concludes that “violence against women is not a very popular sexual fantasy for males”. Regardless of which of these opposing views were closer to the truth at the time there is little doubt that the content of pornography has changed in recent decades and has, in many people’s minds, become more violent and extreme.

According to Dines (2010: xvii) pornography’s images today have “become so extreme that what used to be considered hard-core is now mainstream pornography. Acts that are now commonplace in much of online porn were almost non-existent a couple of decades ago”. Similarly a content analysis study by Bridges et al. (2010) which analysed the content of dozens of best selling pornographic films found that acts coded as ‘aggressive’ took place in almost 90% of scenes. As they write:

On the whole, the pornographic scenes analyzed in this study were aggressive; only 10.2% of scenes did not contain an aggressive act. Across all scenes, a total of 3,375 verbally and physically aggressive acts were observed. Of these, 632 were coded as instances of verbal aggression and 2,743 were coded as instances of physical aggression. On average, scenes had 11.52 acts of either verbal or physical aggression and ranged from none to 128. Physical aggression was much more common than verbal aggression, occurring in 88.2% of the scenes, whereas expressions of verbal aggression occurred in 48.7% of the scenes. By far, the most common verbally aggressive act was name calling (e.g., “bitch,” “slut”). Spanking (35.7% of physically aggressive acts), gagging (27.7%), and open-hand slapping (14.9%) were the most frequently observed physically aggressive acts. Other physically aggressive acts recorded included hair-pulling (10.1%), choking (6.7%), and bondage or confinement (1.1%) (Bridges et al., 2010: 1075).

The definitions of ‘violence’ and ‘aggression’ used in this study are naturally open to debate and other studies into the content of pornography have used differing or more limited definitions of these terms. What is harder to dispute however is the information which Bridges et al. (2010: 1076) have gathered on the distribution of aggressive acts by gender. Women, they write:

were overwhelmingly the targets of aggressive acts. Across all acts of aggression, both physical and verbal, 94.4% were directed toward women. Men were the perpetrators of aggression more than twice as often as women, committing 70.3% of the aggressive acts recorded. In contrast, women were perpetrators of 29.4% of all aggressive acts. Even when women were perpetrators, their targets were frequently other women (17.7%). Men were targets of only 4.2% of aggressive acts perpetrated by women.

Those acts of violence listed in the above study can perhaps be seen as just one of many ways in which porn exemplifies, recreates and reinforces the gender roles and norms prevalent within wider society. Sex under patriarchy is conceptualised, radical feminists would argue, as an act of male dominance over women and the role of women during sex is believed primarily to be that of pleasuring men. Pornography may help, as some of its supporters argue, to break down the traditional notion that women don’t or shouldn’t enjoy sex, but it does not in any way shatter basic patriarchal norms of male dominance and female submission. On the contrary it eroticises them and places new demands on women to, not just accept, but to openly embrace and appear to enjoy their expected roles under patriarchy. As Dines (2010: xxiii) points out:

The messages that porn disseminates about women can be boiled down to a few essential characteristics: they are always ready for sex and are enthusiastic to do whatever men want, irrespective of how painful, humiliating, or harmful the act is. The word ‘no’ is glaringly absent from porn women’s vocabulary. These women seem eager to have their orifices stretched to full capacity and sometimes beyond, and indeed, the more bizarre and degrading the act, the greater the supposed sexual arousal for her… Even though these women love to be fucked, they seem to have no sexual imagination of their own: what they want always mirrors what the man wants.

- Pornography and its users

An issue that took prominence at the time of the ‘feminist sex wars’ was pornography’s relationship to rape and other forms of sexual violence and its impact on the attitudes and behaviour of its users. Supporters of pornography often demanded proof of it as a direct cause of rape, using the apparent absence of any clear evidence as a pretext for denying that pornography had any effect at all. As Jensen (2007: 102-103) points out the issue is far more complicated than a straightforward assertion that pornography either does or does not cause rape and to prove either one way or the other through the use of laboratory studies is extremely difficult, if not impossible. The methods used in such studies, and the pervasiveness of pornography within society as a whole, make them unreliable for such a purpose. Despite this it would nevertheless be a mistake to completely discount the usefulness of research studies in the field of pornography. A meta-analysis of over thirty studies into the effects of pornography found, for example, that watching it led to an increase in aggressive behaviour amongst the viewer while another of forty six separate studies found that pornography increased the likelihood of its viewers committing sex offences, accepting rape myths as true and having problems in their personal relationships (Banyard, 2010: 161-162).

For a more sophisticated analysis we need to consider pornography’s role in upholding what some have referred to as a ‘rape culture’. By this it is meant a society in which rape myths are prevalent, male violence endemic, and where men commonly believe they have a natural right to pressure women into sex or make demands of them to that effect. All the evidence, it could be argued, points in the direction of us living in such a society. A recent study in Toronto found, for example, that 54% of the women interviewed had been sexually abused by the age of 16 (Jensen, 2007: 49). In another study exploring women’s experiences of sexual abuse only 27% of those who had been subjected to behaviour legally defined as rape chose to define themselves as rape victims, suggesting that such behaviour is normalised to the extent of it becoming invisible (Jensen, 2007: 48). Pornography, it can be argued, feeds into and reinforces the very attitudes that lead to male violence in the first place and is an increasingly important factor in the socialisation of young males under patriarchy. According to Dines (2010: 86):

As boys grow up as men, they are inundated with messages from the media, messages that both objectify women’s bodies and depict women as sex objects who exist for male pleasure. These images are part and parcel of the visual landscape and hence are unavoidable. They come at boys and men from video games, movies, television ads, and men’s magazines, and they supply them with a narrative about women, men and sexuality. What porn does is take these cultural messages about women and present them in a succinct way that leaves little room for multiple interpretations.

Young women too have come to view porn in large numbers but their relationship towards it differs in a number of ways. A survey of Swedish teenagers, for example, when inquiring about their attitudes to pornography, found that 71.6% of young women answered ‘quite’ or ‘very’ negative as opposed to 22.6% of young men. In addition 68.6% of females said that the position “pornography is degrading” was something they agreed with either entirely or to a large extent. The comparable figure for those males surveyed meanwhile was 37% (Medierådet, 2006: 38). Finally when asked whether or not they felt ‘turned on’ as a result of watching pornographic films 32.6% of young women answered either ‘quite’ or ‘very’ as opposed to 74.4% of young males (Medierådet, 2006: 40). It would be reasonable to conclude from the study that young people of both sexes hold often mixed views towards pornography with some considering it both to be arousing and degrading at the same time. There is however a huge gap between the attitudes held by men and women and a clear majority of women, unlike men, would appear to see pornography in a negative light.

In a society where sexual violence and abuse is endemic and where women increasingly feel pressured to completely remove their pubic hair (Walter, 2010: 108) or to perform acts such as anal sex for their partners despite finding it painful (Flood, 2010: 171), it is increasingly important that a critical perspective towards pornography is heard. Young women, according to the study above, largely see pornography as ‘negative’ and ‘degrading’ while young men are socialised, partly through pornography, into a belief in their own sexual superiority and right to demand certain acts from women. Despite this there has been, according to Walter (2010: 106), a “muffling of dissent around pornography” and many are unwilling to criticise porn for fear of being derided as ‘prudish’, ‘puritanical’ or ‘anti-sex’. Pro-porn feminists, it can be argued, regularly contribute to the silencing of any critical debate around the role of pornography by falsely dismissing their opponents as ‘conservative’ or ‘right-wing’ or attributing their hostility towards commercial pornography to a fear of sex per-se (Jeffreys, 1990: 268-269).

- Conclusions

Pornography is an issue which has, both historically and in the present day, been the scene of bitter disputes within feminism. As has been argued, some of these disputes have emerged out of a different understanding, between the two sides, of the role of power inequalities and of those capitalist and patriarchal structures which shape, and serve to restrict, our choices in life. To argue, as many supporters or defenders of pornography do, that only absolute freedom to the individual will allow women to express themselves sexually, or to challenge male-dominant assumptions about sex, is clearly misleading in a world where power, wealth and access to the media are distributed to such an uneven degree. Only once genuine sexual justice and self-determination have been achieved by women shall both sexes have an equal opportunity to, through pornography and other forms of media, express themselves sexually and to influence, define or abolish those gendered roles, norms and assumptions which exist within the sexual sphere. The mere entry of more women into positions of power within the porn industry under patriarchy would not necessarily lead to any positive change since, in the words of Corsianos (2007: 875), “identification within… (hetero)sexist ideologies is so pervasive, so internalized, that many ‘women’… believe they are the authors of their life’s scripts and that they are free to choose how they will define themselves sexually, which includes their sexual performances”.

The massive expansion of the sex and porn industries in recent decades and the ongoing pornification of popular culture makes a critique of pornography more relevant and important than ever before for those feminists concerned with bringing about fundamental change in the prevailing roles and norms around gender and sexuality. Pornography, as argued above, has become increasingly violent and, in its most common forms, serves to reinforce and recreate ideas of male dominance and female submission and of women’s supposed role of existing to serve men sexually while making little or no demands of their own. While strong reservations about pornography and its role in society continue to be felt by many these are often silenced, ignored or ridiculed by a patriarchal discourse which denounces any criticism of male-dominant sexuality as ‘puritanical’ or ‘anti-sex’.

I have focussed, in this essay, almost exclusively on mainstream, commercial, heterosexual pornography and it would be wrong to see this as representative of all porn in existence either now or in the future. Some feminists advocate, for example, the production of alternative forms of pornography to challenge those hegemonic images of gender and sexuality endlessly promoted within patriarchal, capitalist society. While automatically dismissing or rejecting such an approach would be a mistake, it is important that feminists who advocate it do so, not as an alternative but rather as a complement to, existing efforts to continually highlight, expose and challenge those images, stories and messages about women, men and sexuality presented by the commercial, capitalist and patriarchal porn industry.

- Bibliography

Banyard, K. (2010) The Equality Illusion: The Truth About Women and Men Today, Faber and Faber: London

Bridges et al. (2010) ‘Aggression and Sexual Behavior in Best-Selling Pornography Videos: A Content Analysis Update’, Violence Against Women 16(10): 1065-1085

Carol, A. (1994) Nudes, Prudes and Attitudes: Pornography and Censorship, New Clarion Press: Cheltenham

Corsianos, M. (2007) ‘Mainstream Pornography and ”Women”: Questioning Sexual Agency’, Critical Sociology 33: 863-885

D.A. Clarke (2004) ‘Prostitution for everyone: Feminism, globalisation and the ‘sex’ industry’ in Stark, C. and Whisnant, R. (eds.) (2004) Not For Sale: Feminists Resisting Prostitution and Pornography, Spinifex Press: North Melbourne

Dines, G. (2010) Pornland, Beacon Press: Boston

Dworkin, A. (1977) ‘Pornography: The New Terrorism’ in Dworkin, A. (1988) Letters From a War Zone, Secker and Warburg: London

Flood, M. (2010) ‘Young Men Using Pornography’ in Boyle, K. (eds.) Everyday Pornography, Routledge: London and New York

Jeffreys, S. (1990) Anticlimax: A Feminist Perspective on the Sexual Revolution, The Women’s Press Ltd: London

Jensen, R. (2007) Getting Off: Pornography and the End of Masculinity, South End Press: Brooklyn

McElroy, W. (1995) XXX: A Woman’s Right to Pornography

Available at: http://www.wendymcelroy.com/xxx/chap6.htm

Medierådet (2006) Koll på porr – skilda röster om sex, pornografi, medier och unga

Available at: http://www.medieradet.se/upload/Rapporter_pdf/kall_pa_porr.pdf

Millett, K. (1970) Sexual Politics, Virago Press: London

Oxford Dictionary (2011) ‘Definition of pornography’

Available at: http://oxforddictionaries.com/view/entry/m_en_gb0649410#m_en_gb0649410

Rubin, G. (1984) ‘Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality’ in Vance, C.S. (1984) Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality, Routledge and Kegan Paul: Boston, London, Melbourne and Henley

Stark, C. (2004) ‘Girls to boyz: Sex radical women promoting prostitution, pornography and sadomasochism’ in Stark, C. and Whisnant, R. (eds.) (2004) Not For Sale: Feminists Resisting Prostitution and Pornography, Spinifex Press: North Melbourne

Stoltenberg, J. (1990) ‘Pornography and Freedom’ in Russell, D.E.H. (eds.) (1993) Making Violence Sexy: Feminist Views on Pornography, Open University Press: Buckingham

Strossen, N. (1995) Defending Pornography: Free Speech, Sex and the Fight for Women’s Rights, Scribner: New York

Sørensen, A.D. and Knudsen, S.V. (2006) Unge, Køn og Pornografi i Norden – Slutrapport, Nordisk Ministerråd: København

Available at: http://www.norden.org/da/publikationer/publikationer/2006-749/at_download/publicationfile

Walter, N. (2010) Living Dolls: The Return of Sexism, Virago Press: London

I am continually of the opinion that pro-porn feminists are weak and cannot let go of petty vices. There’s no possible way to look at porn and not see horrible, horrible violence and extreme displays of patriarchal dominance unless you’re ignorant or in denial.

Even in “lesbian” porn there is a male role and a female role. Words like “slut” and “bitch” are used, and it’s a very prevalent theme that enjoying sexual pleasure is something to be felt guilty about if you’re a woman. Same with scenes with two men, where one will take on a submissive role. Any behaviour where a role of higher importance or power is present is unhealthy behaviour.

Not to mention the fact that it’s not freedom of speech at all. Young deluded girls get conned by social pressure into going into say, glamour modelling for some rag, then when they’re sucked in by the compliments and self esteem boost, they get offered more money to do things that would make them cringe or boak otherwise. People just watch it and jack off to it thinking that the “actors” are loving it too, when in reality they’re behind the scenes dreading their next piece of work and what it will entail. And then you have the fools that will ask “Then why don’t they just leave?” How hard do you think it would be to get a job after you’d been in porn?

I think it was a brilliant piece of work and I know it was an essay and maybe then had to be somewhat balanced, but I disagree with your closing musings about perhaps having porn that is acceptable. I think it’s entirely wrong even from a non-feminist perspective to be viewing people are tools to your own pleasure. I do not think that porn can exist if we have total equality. The people viewing porn will always have the power to switch off the film, power to leave the theatre and power to edit the footage and use it in any which way they want, whereas the actors have no power over it when it is released into the world.

Thanks for your comment LT.

I think your fears about any kind of porn are well founded and there is absolutely the danger of people being objectified and seen as tools even in a pornography which was not produced in an exploitative way or which depicted a genuinely non-patriarchal sexuality. I don’t think all forms of erotic material are wrong per-se and to get rid of it completely is clearly impossible but for as long as we live in an unequal society in which people frequently see others as objects they can use or take advantage of it’s likely that porn of all types will be used in a negative and damaging way.

That said I do perhaps feel that it would be positive and helpful to the fight against patriarchy if we had a wide range of erotic material that portrayed a sexuality that was genuinely egalitarian and in which people saw each other as equals deserving of love and respect. At the moment when young people look up sex online they are bombarded with images of hatred and contempt and in that respect it would definitely be an improvement if instead they could find images or films of respectful sex between equals. The question is perhaps whether or not that is even possible in the fucked up world we live in at the moment.

I really like your comment Lydia, I’ve always thought it’s probably impossible to get non-exploitative porn but I’ve never really known exactly why, and your point about the people viewing it always having the power in that situation, the ‘actors’ are always just a tool for someone else’s enjoyment, they have no real agency in that. They don’t get to decide who views it and whether they’re objectionable or not, unlike how in theory we get to decide who we engage in sexual acts with.

I have a single question for yall – what, in your opinions, causes sexism? By which I mean what is its root cause? And if your first answer was going to be simply patriarchy then what causes patriarchy?

I don’t think there’s any simple answer to the ‘root cause’ of patriarchy, but Helene Cixous has argued that patriarchy is caused by a certain (philosophical/ideological) understanding of the world that privileges traditionally ‘masculine’ values over traditionally ‘feminine’ ones: “There is an intrinsic bond between the philosophical … and phallocentrism. The philosophical constructs itself starting with the abasement of women. Subordination of the feminine to the masculine order which appears to be the condition for the functioning of the machine”. She uses language as her example, demonstrating that language is constructed of hierarchical, binary oppositions, where the ‘masculine’ is always privileged above the ‘feminine’. Of course the idea of concepts as ‘masculine’ or ‘feminine’ are constructs, but they are constructs which are real and have a long history of reinforcement. Cixous draws on Derrida’s belief that the history of thought is tainted throughout with what he calls ‘logocentrism’, a concept which can be teased from between the lines of Of Grammatology if you have the patience for it. For Cixous logocentrism and phallocentrism are closely related, she explores this vision of history in Sorties, which can be found within The Newly Born Woman or New French Feminisms (eds Elaine Marks and Isabelle de Courtivron). She writes: “If it were to come out in a new day that the logocentric project had always been, undeniably, to found/fund [same word in french] phallocentrism, to insure for masculine order a rationale equal to history itself?” I don’t think she’s trying to pose this as necessarily a conscious or deliberate move, but as a powerful presence no less. This chapter doesn’t ‘explain away’ the dominance and creation of patriarchy, but it does offer something towards an answer.

There is undoubtedly much abuse and exploitation in the production of commercial porn.

But is all sexual attraction objectionable because it objectifies who is found to be attractive ?

What is sexual attraction and sexuality all about…… ?

Here’s article by socialist feminist Lynne Segal -

http://www.zcommunications.org/talking-straight-reclaiming-hopes-for-womens-sexual-liberation-by-lynne-segal

This is a fairly reasonable overview piece, but in general it truly infuriates me how BOTH sides of this debate insist on being so bloody absolutist. To be honest, I find anyone who truly takes a straighforward, confident, unshakeable pro- or anti- stance on this particular issue somewhat distasteful and dogmatic – it’s an issue that is SO problematic on SO many levels and it tends to be depressingly oversimplified on both sides. I think it’s too obvious for words that the majority of pornography produced in the world is sexist and exploitative. That, in itself, tells us absolutely nothing about pornography, it simply reiterates what we already know – that we live in a sexist and exploitative world. To think about pornography *as a concept*, however, I think is very, very, very difficult for a lot of feminist thought, and I don’t actually know if I’ve ever come across any satisfactory work that has truly achieved this. The pornography debate CANNOT be reduced to a condemnation of the porn industry’s abuses, or of the psychological effects of watching too much porn, and so on and so forth; these are important debates in themselves, but they are not the entire debate. The issue goes a hell of a lot deeper than that: it’s an issue about, among many other things, the entire nature of human desire, about female sexuality, about feminist sexuality, about the sexual imagination and about the commercialisation of the sexual imagination, and about how we can possibly incorporate all of this into our politics. And these are such incredibly complex problems that I don’t think anyone has ever come close to solving them, especially since we are necessarily confined to discussing them within the framework of a patriarchal world, and to conceptualise beyond that world is a lot more difficult than I think a lot of people would like to admit.

Now, I just want to point out a few problems I have with LT’s comment: “I am continually of the opinion that pro-porn feminists are weak and cannot let go of petty vices”. Now, if by ‘pro-porn’ you’re talking about people who take a completely unqualified stance that ALL porn is ALWAYS fine and shouldn’t even be discussed, then sure, that’s a bit of a rubbish stance. But I don’t think most intelligent ‘pro-porn’ feminists think in any such way – in fact, most of us who don’t take your side actually have an incredibly difficult and ambivalent relationship with this issue and with our own sexuality in general, and to dismiss a huge aspect of other women’s sexuality as ‘weak’ and ‘petty vices’ is a very dubious thing for any feminist to be doing; it’s exactly the kind of language that gets this strand of feminism unfairly associated with puritanical conservatism. Not that I’m saying we shouldn’t interrogate and politically question our own desires – I agree that the Gayle Rubin-style ‘anything goes’ approach to sexuality is stupid, naive and not particularly feminist. But neither do I think simply repressing certain aspects of desire because they go against received feminist wisdom is healthy or politically productive. The rest of your post does what I’ve mentioned above – focuses entirely on the conditions of porn production in our present state of society, and remains adamant that non-patriarchal porn is unimaginable. This, to me, is a very unsettling conclusion, because it seems to imply that patriarchy itself is untranscendable. I see no good reason why, if we can aspire to a world where gendered power structures and sexual exploitation (and of course exploitation in general) have been abolished, we can’t see any place in that world for (to use Stuart’s explicit definition) “printed or visual material containing the explicit description or display of sexual organs or activity, intended to stimulate sexual excitement”. Of course, to produce non-patriarchal porn in a patriarchal world is a much more difficult task, but I think to say it’s impossible is again to suggest that patriarchy is an utterly monolithic, totalising force that can never be subverted, which is patently nonsense, because if it were true there would be no point in being feminists at all. Personally, I would love to see more people actively trying to produce real feminist pornography (preferably in a non-commercial context) that’s erotically exciting AND politically engaged (furthermore, I don’t think porn and art should ever be seen as mutually exclusive). This is incredibly rare, of course, but c’mon, surely you don’t join a socialist party without a bit of utopian imagination…

In response to Fitta:

I disagree with porn in it’s entirety because it’s inherently sexist. Porn was not something invented in a neutral and equal founding and was hijacked by patriarchy. It was created by men for men, and I really don’t think it’s justifiable to say that women need it tailored to them. I’d like to reinforce my point again about porn being wholly exploitative – not just for women, but for men too. Obviously women have it a million times worse, but men who act in “gay” porn are also hugely exploited. My point is that when you watch porn, those are not people you are seeing, but tools to peoples’ enjoyment. There is nothing anyone can do to make that not so, unless you put their clothes on and take away the sex. But then it’s just a soap opera.

Sexual pleasure is a very different concept to other human needs/emotions. Although, I use the term “need” loosely because I do not think that humans NEED sex. Humanity needs sex, but the individual does not. When we start seeing things like sex and pornography as our right, then we immediately tip the scale of equality and someone needs to be exploited to make that happen.

I believe shouting about a very unattainable situation (female-friendly porn in a utopian world) is a foolish way to fashion your stance now, in a world of exploitation and oppression. We’re not going to make violence and oppressive porn go away by supporting it.

I’m exclusively anti-porn because I believe porn is exclusively anti-women.

@ Old flame

I think the article you post is damaging and simplistic in its continued attempts to insult and silence radical feminists, accusing them of being “sexually repressed” and setting them in opposition to the struggle for sexual liberation. That’s not to say it doesn’t make some valuable points but on the whole it leans too far in the direction of downplaying the role of patriarchy and male domination and trying to make us believe that things aren’t as bad as they are. I’m in agreement that we need to talk far more about what a genuinely egalitarian and liberated sex between men and women would look like but we won’t get there without a clear understanding of how deeply ingrained the structures and ideologies of patriarchy and heteronormativity really are.

“We’re not going to make violence and oppressive porn go away by supporting it” – I think I made it entirely clear that I don’t ‘support’ violent and oppressive porn. I strongly support attempts to create NON-oppressive porn, as both an alternative to and a critique of the mainstream porn industry. But I guess we very fundamentally disagree about the basis of the argument. The porn industry was, indeed, created ‘by men for men’ (so was the entirety of Western culture and philosophy, by the way, but I’m not sure that means we should want to abolish all art); but I’m talking about pornography as a concept distinct from that industry – that is, as any material (whether visual, written, auditory, or anything else) designed for the main purpose of erotic arousal, although not necessarily the sole purpose – as I pointed out before, I think porn can and should be artistic and political. Out of curiousity, how do you feel about, for example, works that are classified as ‘art’ rather than ‘porn’ but which have an explicitly erotic element, and which can and do sexually arouse those who view them? Have you ever been turned on by a sex scene in a film? Should there even be sex scenes in films? Or is it the fact that porn is ONLY (or at least, mainly) about sexual arousal that makes it inherently wrong? Would you say ‘erotica’ is something different from (and more acceptable than) porn? I’m asking all of this out of genuine curiousity, because yours is a position I find quite incomprehensible. Physical attraction, visual stimulation, and performative fantasy are a HUGE part of human sexuality (both male and female) and I find it frankly bizarre that anyone could think that was wrong in and of itself. To say pornography itself (not the industry) is ‘inherently sexist’ suggests that women are not and more crucially never can be active, gazing, self-determining agents of their own desire, that women can never take pleasure in voyeurism, that men’s and women’s ways of desiring are somehow fundamentally and unresolvably *different*. And I find that a deeply patronising oversimplification. Personally, I watch very little porn for the obvious reason that it’s near impossible to find anything that isn’t depressingly misogynist. But, if I can find it, I enjoy watching and being aroused by two people having affectionate, consensual, convincing and passionate sex, as do a great many women. What exactly is ‘inherently sexist’ about that?

Your point about seeing people as ‘tools’ is a more interesting one, and definitely true for a lot of people (particularly men) who watch a lot of porn. But I’d argue that any such attitude is just part of a much larger culture of sexual objectification, particularly as a condition of masculinity, and as such, porn really isn’t the root of the problem but just a particular branch of sexual culture where the problem is more explicitly manifest. Furthermore, the pleasure of looking is a huge part of both male and female sexuality, and I can’t bring myself to see anything inherently exploitative about watching and appreciating the erotic beauty of other people’s bodies, provided, of course, that the people I’m watching have given full and free and enthusiastic consent to being watched and are actually enjoying themselves – and for me a major condition of my enjoyment of pornography is specifically that the people ARE people, that they both express real affection, real enjoyment, active desire and aren’t just a pile of flailing limbs and jiggling tits. Obviously this is the problem with porn as a commercial product – it’s difficult to identify what counts as real consent/enjoyment when money is in play, so yeah, I’m pretty uncomfortable with commercialised porn, but then, I’m pretty uncomfortable with commercialisation in general, so this isn’t much of a special case.

Here’s the crux of it, though: the idea of all porn being female-friendly is, quite obviously, unattainable and utopian at this point in time. But so is the idea of abolishing porn. The internet exists. Porn is not going away any time soon. Given this state of affairs, whatever your personal attitude to porn, don’t you think it’s vastly more productive and desirable that feminists should feel able – without being made to feel like bad feminists – to create female-focused pornography on their own terms, to express as Stuart puts it above a “wide range of erotic material that portrayed a sexuality that was genuinely egalitarian and in which people saw each other as equals deserving of love and respect”? I think this is actually absolutely crucial at this point in history: porn is such a huge part of so many people’s sexual development, and a lot of those people wouldn’t necessarily seek out or favour the kind of ‘mainstream’ porn that fetishises power and degradation – the problem is, it’s just what’s there, and there are very few real alternatives. And I really think that this is dangerously inhibiting for people who might otherwise be exploring their desires in a much more healthy, caring, and ultimately pleasurable way.

I thought the Segal article was pretty great, actually, though I’ve only had time to skim-read. Could you point out where exactly she tries to ‘silence’ radical feminists? As far as I could tell she was only saying that certain strands of radical feminist thought are too simplistic and reactionary in their account of both male and female sexuality, and that they don’t adequately allow for “the complexity, ambivalence, and unsettling elements of power and submission present in all desire–female as well as male”. I’d say she shows a pretty acute awareness of the structures of patriarchy and even more so heteronormativity (most of the article is based on radical lesbian critique ffs), and makes it quite clear that she doesn’t think ‘liberation’ is a straightforward and unproblematic path.

“Even in “lesbian” porn there is a male role and a female role. Words like “slut” and “bitch” are used, and it’s a very prevalent theme that enjoying sexual pleasure is something to be felt guilty about if you’re a woman. Same with scenes with two men, where one will take on a submissive role. Any behaviour where a role of higher importance or power is present is unhealthy behaviour.”

because one partner taking a submissive role and one taking a dominant role in same sex relations never happens in real life ? and equating the dominant role in sex with inherently being a “Male” role ? kind of an ironic statement to come from a feminist is it not. sorry but most of the people commenting on here sound like they have never really seen any porn (or at least would rather come out with the conservative lines expected of them than admit it and give an honest opinion, something I imagine allot of male leftists would do when discussing the issue in the presence of female feminists), all I see is the same ignorance about the subject on the more progressive side of politics that you do on any other, am I saying porn is not and can not be misogynistic, abusive to woman and people in general no, what I am saying is there are ALOT of different kinds of porn and trying to cram it all into a frankly ignorant “its all violence and take it dirtyslutbitch” opinion is lazy at best and reactionary at worst.

Some interesting points, fitta.

I chose here to use a very broad definition of pornography – I know some radical feminists (ie. Diana Russell) distinguish between pornography (as something purely negative and exploitative) and erotica (as something positive and egalitarian) but I don’t actually think the term we use is that important as words can clearly change their meanings and conceptions over time. One potential problem perhaps with the word ‘porn’ is that people at the moment have a clear idea of what it’s ‘supposed’ to look like and involve and any attempts at creating an alternative will likely be judged in relation to these criteria – but then you can probably say the same about all expressions of sexuality in today’s society.

I think it’s reasonable to distinguish between porn produced commercially for a profit and that which was produced, say, by the mutual and active consent of two or more people for the purpose of expressing their own genuine desires and/or political visions. As I see it there is no way the commercial, capitalist porn industry can ever be justified from a feminist perspective and, as LT points out, it inevitably involves people being seen and treated as tools for the profit or enjoyment of others. Commercial porn is no different from prostitution and will always involve people being coerced, through money, into doing things they wouldn’t otherwise do or enjoy.

I think it’s undoubtedly true that porn plays a significant role in a lot of young people’s ‘education’ about sex and at the moment there’s basically no alternative. Even if we had extremely comprehensive sex education (which would at least offset some of the lies and myths being spread by the porn industry) people would still want to look for more erotic depictions and images and when the only ones available tend to be deeply misogynistic and male dominant it’s hardly surprising that that’s the type of sex so many find arousing or feel pressured into participating in.

I definitely don’t think trying to produce alternative porn (when it will likely be vastly outnumbered by the mainstream, misogynistic variety) is, in itself, an adequate or sufficient solution to the problem but, when combined with the fight against the commercial porn industry and its images of misogyny, it may well help in the development of an alternative, non-patriarchal outlook with regards to gender and sexuality.

With regards to the Segal article I think it is indeed a silencing tactic, as I point out in the essay, whenever supporters or defenders of porn (among which Segal can definitely be counted) accuse radical feminists of being “sexually repressed”, reinforcing the very same ideology that makes a lot of women scared to criticise pornography and other forms of sexual exploitation in today’s society. I’m not saying there’s no complexity at all in the relations between women and men, but to overemphasise the supposedly ‘ambivalent’ nature of patriarchy is to downplay men’s dominance and abuse of women and risk leading people to falsely believe that we can build a better world without fundamentally changing and abolishing the structures of inequality and oppression on which our current one is so clearly built.

Could I ask if any of the opponents of all pornography are proposing to outlaw/criminalise the production and/or consumption of everything considerd “pornographic” and , if so , how that might be done in practice ?

Erm, but again, I’m not sure where she actually does any of that? Maybe I missed it from skim-reading but can you quote the part where she calls radical feminists ‘sexually repressed’? She certainly says that there are large elements of radical feminist theory and politics that are sexually repressed/repressive, which is an entirely valid claim, but I don’t see any of the kind of ad hominem attack you keep accusing her of… I think that it’s equally a kind of silencing tactic to leap on anyone who dares to question any element of radical feminist wisdom as being ‘simplistic’, or having ‘false consciousness’, or not fully ‘understanding’ the reality of patriarchy, or ‘downplaying’ inequality. I mean, the article itself deals with all your points, here and elsewhere: “I am not suggesting, however, that the struggle to break the codes linking active (“masculine”) sexuality to cultural hierarchies of gender will ever be easy. Sex and gender hierarchies have survived despite their increasingly obvious contradictions. It is a trap to assume (with the Cosmopolitan-led, fashionably feminine layer of mass-culture) that we can ignore both the symbolic dimensions of language and the existing relations of power between women and men. In Cosmo and its ilk, women are presented as already the equal sexual partners of men, and told how to obtain and please their men, as if men were all seeking much the same advice. Such rhetoric nonchalantly neglects the extent of men’s power over women, and its defensive facade of endemic misogyny: apparent from the merest scratch on the liberal surface of sexual equality.”

Here’s the thing: I think often defences like yours make the bizarre assumption that anyone who questions the received feminist ideas about pornography and sex is somehow trying to compete with the progresses of radical feminism, to set ourselves against it. That is utterly not the point. The entire point is to enhance and revise and think dynamically about these issues WITHIN the framework of a radical feminist consciousness, without the fear of being dismissed by other feminists as ‘weak’ or ‘silencing’. Of COURSE I agree that producing alternative form is not an ‘adequate or sufficient solution’ to the problem; I don’t think any feminist does, and again, to suggest that we think this feels like another silencing tactic in itself. I mean, maybe I’m being naive, but when I’m debating in a feminist discourse with other feminists, I take it as an incredibly obvious given that we are all on the same page when it comes to fighting against the real abuses and violences of a patriarchal society. I didn’t think that was something that was even up for debate. The point that I, and women like Segal, are trying to make is not that we should undervalue or turn our backs on that fight; the point is that the world and sex and gender relations are too complicated to be entirely reduced to the fight against overt misogyny, that the sexual and social experiences of real women are complex and ambivalent and problematic in a whole lot of ways that have nothing to do with straightforward sexist abuse or straightforward patriarchal conditioning, and as such, that the terms of discussion need to expand to allow us to discuss and account for those experiences and where they fit in to our vision of equality. Condemning and preventing abuse and sexism is obviously always going to be a major element of any feminism, but I can’t help but feel any feminism that founds itself *solely* on that basis is necessarily exclusionary and incomplete.

Oh, and I very much agree with you on the point about defining ‘pornography’. The porn I’m talking about is what some people would probably prefer to call ‘erotica’, but I think it’s generally an arbitrary and actually somewhat snobbish distinction – the term ‘erotica’ has undertones of faux-artiness and elitism and I tend to associate it with an unpleasant attitude of ‘our desire is better and more sophisticated than yours cos it’s more subtle and shot in black and white’. To define ‘erotica’ as something inherently more feminist than ‘pornography’ is just a false revision of a word that definitely doesn’t have that meaning in its wider use – as far as I can tell ‘erotica’ usually just signifies ‘soft’ or more artsy porn, rather than having anything whatsoever to do with the gendered content, so there’s no reason why it can’t be equally as exploitative and misogynist as porn.

@ old flame

I can’t speak for everyone here but I personally think banning or eradicating all material deemed ‘pornographic’ is both impossible and undesirable. I would, on the other hand, very much support laws against the commercial porn industry. The SSP already supports the Nordic prostitution model and I would like to see this extended to the purchase of all sexual acts and services, including through porn. That way it would be made impossible for porn companies to legally pay individuals to perform in their films. I also think there should be laws against misogynistic hate speech and incitement to gender hatred but it could obviously be difficult to draw up a clear definition of what such a thing involves in the context of porn.

@ fitta

Segal accuses radical feminists (and particularly Catharine MacKinnon) of spreading a “brand of sexually repressive feminist rhetoric”. I think this is a misleading and unwarranted accusation which plays into patriarchal society’s silencing tactics used against women who reject the right of men to use and exploit their bodies. It is fair enough perhaps to suggest that some radical feminists don’t always leave enough room for discussing more positive forms of sex between women and men but to say that this stems from being ‘repressive’, ‘puritanical’ or against all sex per-se is just wrong and serves as a conscious attempt to divert attention away from the real and important issues and critiques that they raise. It must be noted that there’s no one, single radical feminist position on everything and I’m not trying to leap on anyone who dares to criticise any or every perspective which has emerged out of radical feminism.

I do think, despite my criticisms, that Segal definitely presents a more balanced account of the issue than you would hear from a lot of American pro-porn ‘feminists’ and the article does, as I said, make some valuable and important points. I’m not suggesting by the way that you yourself think alternative porn is a sufficient solution for countering the images and messages of the mainstream porn industry. Unfortunately, however, a lot of pro-porn feminists do seem to spend all their time attacking radical feminists and condemning the evils of ‘censorship’ while doing nothing to critique the patriarchal and misogynistic narrative of the capitalist porn industry or to suggest practical solutions about how we can counter it. I’m sure both of us can agree that such a position is simplistic and completely insufficient in a deeply exploitative and male-dominated society.

I’m not saying things aren’t at all complex or ambivalent but I think there’s been far too much emphasis on this in recent years, largely as a result of the ascendancy of post-modernist ideology. I think therefore it is important and, in many ways, positively liberating to return to a discourse which more clearly acknowledges the role of structural inequalities of power and wealth, and the persistence of patriarchal, capitalist ideology, in restricting our choices and opportunities in life.

I think so assume that no one has viewed pornography at any point in their lives is foolish. In my life before feminism, i viewed pornography and it fucked me up enough for me to appreciate a healthy view about it – which is to not have it.

The SSP, in addition to our position on prostitution, also takes a position on commercial sexual exploitation, which would include commercial porn.

There is a distinction to be made between the production of sexually explicit material and its consumption. Workers (male and female) in the porn industry are sexually as well as economically exploited, but the same cannot always be said for those who make such material for non-commercial purposes. Creating sexually explicit material through a desire to do so, is a perfectly valid thing to do.

The content of porn is a serious problem, the messages it sends out about what sexually desirable bodies look like, how people treat each other sexually and what is sexually acceptable both creates expectation and shapes desire in a way that is deeply unhealthy – creating problems in the consumption.

Sexually explicit material, in and of itself, is not offensive even when it is designed to arouse; the problem is with the methods of production and the manner in which it shapes sexuality.

Good that the SSP takes a position on this too Mhairi. I don’t think there’s anything specific in the manifesto so I don’t know exactly what form it would take but if there’s any future discussions I definitely think a more comprehensive version of the Nordic model would be worth considering.

In response to your earlier comment Chris I think you’re missing LT’s point. She’s not saying that dominant/submissive roles don’t exist within same sex relationships in real life, rather that porn seems incapable of portraying any type of sex at all without such a dynamic present. And it is extremely fair and accurate to point out that these roles throughout history have been highly gendered and continue to be today. There is no doubt that much gay and lesbian porn attempts to directly emulate the roles and power differences present in heterosexual porn with one of the participants acting in a traditionally masculine and the other in a traditionally feminine way.

I believe firmly that until these gendered roles of male dominance and female submission have been totally eradicated we will never be able to achieve meaningful liberation and equality within wider society. We should also be trying to change the way in which the entire concept of sexuality is constructed and perceived, challenging the notion of it as being something that one person does to another and instead championing a sex based on equality and mutual respect. In order to do so we can’t possibly allow porn as it currently exists to be left unchallenged.

I don’t think anyone has said that 100% of all porn is unambiguously violent and demeaning but is the study I quote in the essay not cause of concern? The one that shows that 88% of commercial porn scenes contain violence and that 94% of this violence is directed at women? I’m sure everyone here has seen porn and is well aware of what it is like so don’t try to claim that you’re the only one with enough knowledge and experience to recognise the supposedly ‘diverse’ or ‘nuanced’ nature of today’s porn.

I think that porn isn’t the question. In essence, porn is showing the reality through the industry of sex, and with it we can view what is the reality about the relationship between a man and a woman. If we take the fight against porn like an item, the fight against patriarchy will be a parody. It will be a struggle against an image. Someone can argue that porn reproduces patriarchy and he/she has reason. But nowadays every relationship between men and women reflect (and for this reason reproduces too) the patriarchy like an structure. If a man and a woman are having a discussion like equals it is only possible if the “man” wants it, and that discussion is a prove of the existence of patriarchy too. Another thing is if we would use the example of porn to show the relationship of dominance to the society. Well, we can do it like a striking form because for a propaganda action would be okay, but i think that if we are trying to advance in popular implication is better take one more daily example. who goes to the supermarket? why? and why that why? In the debate about the fact and the image i always tilt for the fact. there is a reason for it, if you change the image not means change the fact, but if you change the fact you sure change the image. And the fact is economic, not symbolic. in the previos example the fact was the time. if women will have more resources than men, would we talk about it? the symbolic analysis can be very interestant to understand how the patriarchy expresses, but we can not forget that the dominance has a material base, and we need to change it. Unless we want fight agaisnt ghosts. today porn tomorrow who knows…

I’m catalan and my english is bad…I’m sorry!

http://xkcd.com/714/

Taking advantage of the ONE opportunity I’ll have to post XKCD on this blog without it seeming off-topic.

In MY porn, hot people scribble intelligent notes in the margins of books written by postmodern postcolonial theorists while some Canadian indie band plays in the background, truestory.

@Meghan: Writing in book margins = WRONG. Would writing on a separate notepad not be a better turn-on?

No, book margins. If that doesn’t excite you, you’re just weird.

Unless seperate notebook is a Moleskin Pacman Edition. Naturlich.

Pacman edition sounds cool, but moleskin = too expensive!

Hello Stuart, I am trying to locate the English version of Kajsa Ekis Ekman’s report on prostitution in Barcelona. I believe it was translated into English. Wioyld you have it?

Martin

Hi Martin, yeah you can access it here: http://www.thefword.org.uk/features/2008/03/how_to_get_an_a_1

Thanks a lot for your translation of the prostitution article by the way. Nice to see one of my articles in a language I don’t understand.

Floor tiles Sydney…

[...]Scottish Socialist Youth » Feminism, Pornography and the Fight Against Patriarchy[...]…