Recent Comments

- Andy Bowden on Class politics or anti-semitic conspiracies? Why David Icke, Ron Paul and Alex Jones are dangerous to the Occupy Movement.

- Andy Mc on Class politics or anti-semitic conspiracies? Why David Icke, Ron Paul and Alex Jones are dangerous to the Occupy Movement.

- declan on For a Radical Independence Movement.

- Andy Bowden on For a Radical Independence Movement.

- arm 'n' hammer on For a Radical Independence Movement.

Tags

afghanistan austerity britain BNP climate change Con Dem coalition demonstration drugs economy edinburgh education elections environment events evil megacorps fascism feminism fighting cuts glasgow greece health internet knobheads Labour Lib Dems moral panic music news police protest racism science SDL sexism sexuality SNP strikes tabloids Tories tv unemployment unions USA war women's rights workers' rightsArchives

- June 2012

- May 2012

- March 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

-

Authors

- admin

- And

- Andy Bowden

- Brogan

- CelticEwan

- David

- David Ward

- Erofeeva

- Euan Benzie

- Frenchie

- ImSpartacus

- Jack

- James McIntyre

- James N

- Kirsty Kane

- Liam M

- Liam T

- lovebug

- LydiaTeapot

- Meghan

- Muzza

- Neil B

- neldo

- Sarah

- Scottish Socialist Youth

- Snowball

- Socialist Pharmacist

- Sophie

- Squeak

- Stuart

- syebot

- TheWorstWitch

- Wavejumper

Tunisia at a crossroads

Paris yesterday - in solidarity with the Tunisian revolution

Few could have predicted how rapidly events would unfold in Tunisia over the past few days. A repressive dictatorship, with any public display of dissent rare and fear of the police widespread, the country has been rocked by mass protests over the past month, as we reported last week.

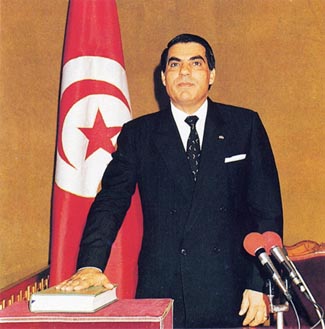

Initially an uprising of urban youth over rising food prices and high unemployment, sparked by the suicide attempt of a young graduate, it quickly developed into a broad front against the regime of Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali, in power for 23 years. As the official organs of civil society entered negotiations with the government – in some cases winning significant concessions – the masses continued to take to the streets, against the threat of bullets, tear gas and imprisonment, raising the chant of “no, no, no dialogue, Ben Alí must go!”

In a desperate bid to cling onto power, on Thursday Ben Ali made a televised address to the nation, in which he pledged not to stand for re-election in 2014 (elections he would have won: in 2009 he took 90% of the vote amid tight media and candidacy restrictions), to introduce sweeping social reforms, and to investigate the police killings of protesters during recent demonstrations.

It wasn’t enough. On Friday, the protests continued. Trade unions called a two hour general strike, and thousands rallied outside the Interior Ministry. A state of emergency was put in place; Ben Ali fired his own government and called fresh elections within six months. On the streets, the police continued to fire live ammunition and tear gas at the now illegal protests. Yet only hours later, reports began to emerge that Ben Ali himself had fled the country – now sheltering as a guest of the Saudi royal family.

But the same political elite are still in power, at least for now. The Speaker of the country’s Parliament has taken the role of interim president, while the army maintain a strong presence on the streets. The new president has promised to abide by the constitution, which states that a new presidential election must be held within 60 days – whether it will prove to more open and democratic than previous elections remains to be seen. Across the country, the army are visibly removing portraits of Ben Ali and other overt signs of his regime. But these changes are superficial, little more than an attempt by the same ruling class to pretend that something has changed, to appease the masses and send them home.

Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali

Ben Ali ascended to the presidency in 1987, when his predecessor was forced out amid a political and economic crisis. What was meant to be an interim measure became permanent, with Ben Ali refusing to cede power. The Tunisian masses are only too aware of this, and will not be duped similarly this time. The events of the past few days have shown that it is the workers, the students and the unemployed of Tunisia who hold the real power – and the future direction of the country is now for them to determine.

The ruling classes are in a state of panic – earlier today the Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi came out and condemned the Tunisian revolt, blaming it on Wikileaks cables deliberately created by US diplomats “in order to create chaos”. The irony couldn’t be greater – President Ben Ali was a firm ally of the United States, a proponent of neo-liberal reform and willing participant in the ‘war on terror’. Gaddafi is terrified because the uprising is already beginning to have an impact throughout the region – in Algeria last week, in Jordan and even in Libya itself. The lessons for the whole of North Africa and the Arab world, and its collection of despotic rulers, couldn’t be clearer.

Tunisia is at a crossroads – one dictator has been forced out, but the revolution has just begun. Socialists in the country now have a key role to play in arguing that the Tunisian people must go beyond simply demanding base reforms to be instituted by another government from the same elite elected through a sham democracy, but that the masses must take power into their own hands. And only this, a democratic system under workers’ control, free from interference by western imperialism, can provide a long-term solution to the day-to-day problems suffered by the people of Tunisia.