Recent Comments

- Andy Bowden on Class politics or anti-semitic conspiracies? Why David Icke, Ron Paul and Alex Jones are dangerous to the Occupy Movement.

- Andy Mc on Class politics or anti-semitic conspiracies? Why David Icke, Ron Paul and Alex Jones are dangerous to the Occupy Movement.

- declan on For a Radical Independence Movement.

- Andy Bowden on For a Radical Independence Movement.

- arm 'n' hammer on For a Radical Independence Movement.

Tags

afghanistan austerity britain BNP climate change Con Dem coalition demonstration drugs economy edinburgh education elections environment events evil megacorps fascism feminism fighting cuts glasgow greece health internet knobheads Labour Lib Dems moral panic music news police protest racism science SDL sexism sexuality SNP strikes tabloids Tories tv unemployment unions USA war women's rights workers' rightsArchives

- June 2012

- May 2012

- March 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

-

Authors

- admin

- And

- Andy Bowden

- Brogan

- CelticEwan

- David

- David Ward

- Erofeeva

- Euan Benzie

- Frenchie

- ImSpartacus

- Jack

- James McIntyre

- James N

- Kirsty Kane

- Liam M

- Liam T

- lovebug

- LydiaTeapot

- Meghan

- Muzza

- Neil B

- neldo

- Sarah

- Scottish Socialist Youth

- Snowball

- Socialist Pharmacist

- Sophie

- Squeak

- Stuart

- syebot

- TheWorstWitch

- Wavejumper

Lancet blasts government over Mephedrone

Doctors: Frustrated with the government's pish

The Lancet, one of the most respected medical journals, has used an editorial to slam the government’s ban on mephedrone.

Under the title ‘A collapse in the integrity of scientific advice in the UK,’ they write:

“There was little time to consider carefully the scientific evidence on mephedrone. The ACMD did not have sufficient evidence to judge the harms caused by this drug class. It is too easy and potentially counterproductive to ban each new substance that comes along rather than seek to understand more about young people’s motivations and how we can influence them. We should try to support healthy behaviours rather than simply punish people who breach our society’s norms. Making the drug illegal will also deter crucial research on this drug and other drug-related behaviour, and it will be far more difficult for people with problems to get help.

The terms of engagement between ministers and expert advisers endorsed by [Home Secretary] Alan Johnson have been blown apart . . . [T]he events surrounding the ACMD signal a disappointing finale to the government’s relationship with science. Politics has been allowed to contaminate scientific processes and the advice that underpins policy. The outcome of an independent enquiry into the practices of the ACMD, commissioned by the Home Office in October, 2009, is now urgently awaited. Lessons from this debacle need to be learned by a new incoming government.”

As well as the editorial, the Lancet features a special report on the ban, which has info from Sweden, where the government has already banned mephedrone:

“David Gustavsson, now at University Hospital of Malmö, Sweden, questions whether experimentation with unstudied substances, especially by inexperienced young people, is because of the misconception that legality implies safety. Adam Winstock [from the National Addiction Centre, London,] also points to the large market of users who are dissatisfied with illicit stimulants and interested in substances with a desired profile of effects, availability, and perceived value for money. Users and community workers suggest that the unavailability or low purity of cocaine and MDMA—related to international control measures—“have contributed to the increase in mephedrone use”, the ACMD cites. Additionally, cathinone derivatives are so-called legal highs and widely available from internet websites, sold as bath salts or plant food, not for human consumption.

Sweden is among several countries that have now banned or controlled mephedrone. Gustavsson recalls that mephedrone use was more frequently reported at Maria Ungdom [hospital, where he worked] from mid-2008, including several users who had encountered “unusual” difficulty stopping mephedrone compared with other drugs. By autumn, 2008, “mephedrone was by far the most popular legal drug sold on the internet in Sweden”, he recalls. Mephedrone was classified as hazardous in Sweden in December, 2008, which restricted internet sale. Subsequently, anecdotal evidence suggests that mephedrone began to be sold person-to-person rather than on the internet, he says.

Stefan Sparring, senior consultant at Maria Ungdom, describes what happened after mephedrone was classified as hazardous: “the drug quickly moved to the illicit trade in the streets, and we still saw new cases every week. In the spring of 2009 it was classed as a narcotic and after that we thought we could see a trend of it disappearing.” However, Sparring still sees new cases related to mepehdrone use every week. “What we now also see is the true emergence of ‘designer drugs”, he notes. After mephedrone became illegal, methodrone flooded the market, he says. Methodrone has since been implicated in two deaths and banned in Sweden. Now, says Sparring, “we have flephedrone instead, and it just continues”.

In other words, the ban in Sweden has not worked, and people are still taking mephedrone. But one of the most interesting things in the above quote is medical experts acknowledging that the interest in mephedrone has a lot to do with the inaccessibility of untainted MDMA or cocaine. Users aren’t interested in “legal highs” because of any inherent respect for the law, but because they know that the illegal, unregulated drugs market means you can’t know what you’re getting. Any attempt to work with drugs users to ensure they know exactly what they’re taking is ruled out by the prohibition policy. As Adam Winstock puts it:

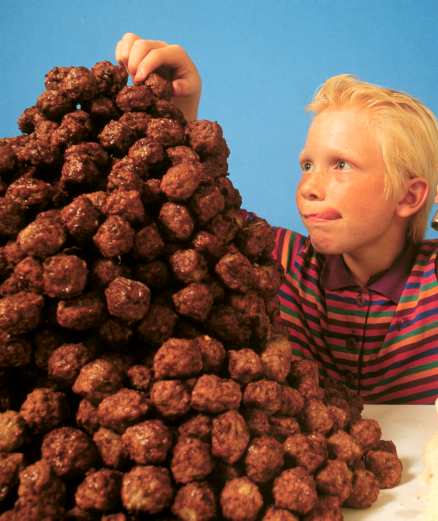

Sweden: Good with meatballs, drugs prohibition not so much

“The lesson we need to learn is, in the case of such drugs, what is the impact of different interventions in harm and use?” he told The Lancet. When a drug is made illegal, controls are limited to supply reduction and keeping harm to a minimum . . . “While in no way does ‘legal’ confer relative safety, it does mean that a broader repertoire of responses is available”, they note.

The Lancet coverage just underlines the scientific bankruptcy of government policy. Drugs prohibition is like the emperor who wears no clothes. Scientists, doctors, drug workers and young people can all see it’s a failed idea and must be scrapped. But when it comes to the political arena, the only political party that can see through the tabloids’ lies and stand by actual scientific evidence is the Scottish Socialist Party.